Rule 1 / Case 4

- Moulton Avery

- Dec 27, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 3, 2025

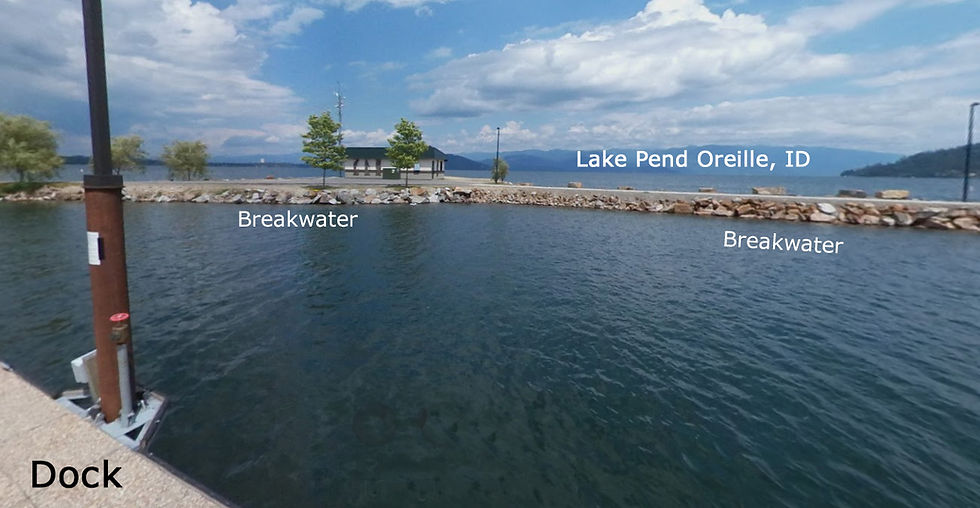

Always Wear Your PFD (Lifejacket) Jim Payne’s Desperate Swim in Freezing Water February 10th, 2012 - Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho

Jim Payne purchased a new folding kayak in preparation for a trip down Chile’s Bio Bio River. When it arrived, he decided to take it for a brief, 10-minute test in a familiar and protected location close to shore: the local marina on Lake Pend Oreille.

Even though it was mid-winter in Idaho, Payne wasn’t particularly concerned about getting out on the water without thermal protection. In 15 years and thousands of miles of paddling, he had never experienced an accidental capsize. Besides, he reasoned, he wasn’t “going kayaking”; this was just going to be a little test. In a safety article that he wrote for Sea Kayaker magazine (December 2012), Payne stated: “The idea of my ending up in the water of a sheltered marina was so remote that I had given it absolutely no thought.”

When he arrived at the marina, a sheet of ice extended out from the shoreline, but the wooden docks extended beyond the ice and provided him with fairly easy access to the water. The docks were about two feet above the water, and this made launching his kayak a little bit tricky. Nevertheless, Payne was able to carefully lower himself into his new boat without difficulty.

It was immediately obvious that his new kayak wasn’t quite as stable as the old one that he was used to, and he rocked it back and forth to get a feel for the difference. Everything seemed OK, so he leaned over a little bit more, just like he'd done hundreds of times before with no problem in his other kayak. However, instead of resisting his movement, his new kayak promptly capsized, spilling Payne directly into the ice-cold water.

The sudden shock of immersion stunned him, but he was able to resist gasping while under water because the combination of his clothing and snug-fitting PFD briefly delayed the freezing water contacting his skin. He then tried the quickest and most sensible route to safety – getting back on the dock. To his surprise, that didn’t work because the dock was too high and the weight of his soaking-wet clothes made it impossible to pull himself up and out of the water. He screamed repeatedly for help, but no one answered. It was a cold, grey, windy day at the marina, and no one saw him capsize or witnessed him struggling to get back on the dock.

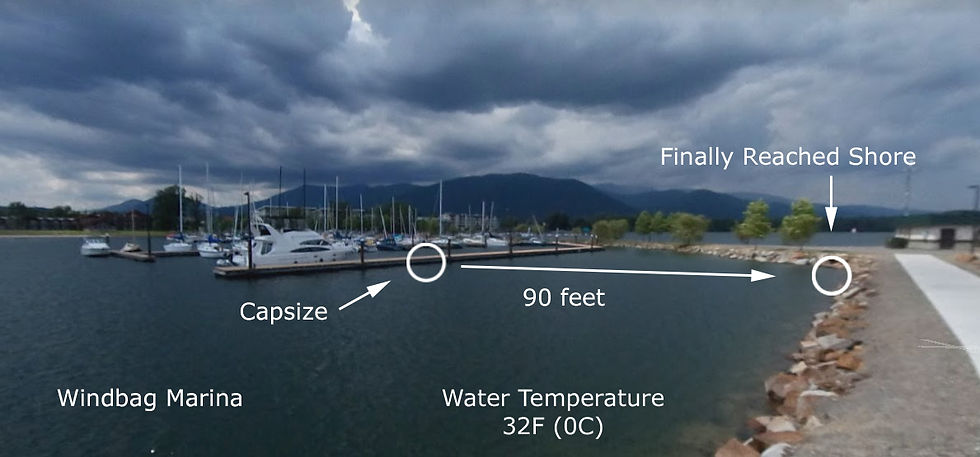

Payne felt like he didn’t have much time left, so he began desperately swimming for an ice-free section of the breakwater that lay 30 yards away. Because of the intense cold and the extreme difficulty he had controlling his breathing, the best he could manage was a slow and very inefficient dog-paddle, which kept his body nearly vertical in the water and reduced his forward speed to about 1 foot every two seconds.

At that pace, it took roughly 3 minutes for him to reach the breakwater. “Panting and convulsing with cold”, he was able to claw his way up the rocks to safety.

Case Note:

There are many valuable lessons to be learned from this incident:

Lesson 1: Had the water temperature been a cool 75F, this would have been a little embarrassing, but otherwise an unremarkable outing. The capsize would have been a non-event, and Jim would have learned – the easy way – that his new boat had less secondary stability than his old one. Instead, a tiny mistake in balance instantly morphed into desperate situation that came within a whisker of costing Jim his life.

Lesson 2: Always wear your PFD. Jim’s upright swimming posture and inefficient dog-paddling stroke were classic signs of swimming failure, and there is no doubt that without the support of his PFD, he would have drowned before he was able to reach shore.

A study of annual open-water immersion deaths in the United Kingdom reported that "approximately 55% occurred within about 3 meters (10 feet) of a safe refuge, and about 42% occurred within 2 meters (6 feet). Two-thirds of those who died were regarded as good swimmers.” In other words, they were unable to swim as little as 6-10 feet in order to save their own lives.

Lesson 3: For someone whose breathing is out of control and who's also suffering the excruciating pain of sudden immersion in 32F (0C) water, 90 feet is a marathon swimming distance - even with the support of a PFD.

Moments after he capsized and tried to get back up on the dock, Jim was afraid that his body temperature was dropping and also that he might lose consciousness within a matter of minutes - a common feeling that can be caused by hyperventilation. The most immediate threats to his life, however, weren't loss of consciousness or hypothermia, they were inhaling water and drowning due to his total loss of breathing control.

This was immediately followed by a desperate swimming challenge: whether his arms would give out due to muscle cooling before he was able to reach shore. In similar conditions, a well-known and very determined cold-water researcher became completely incapacitated after six minutes and had to be pulled from the water after swimming only 50 feet.

Lesson 4: At 72 years of age, Jim also faced the very real possibility of suffering a heart attack or stroke – not when he finally reached shore, but the moment he hit the water. This is because the constriction of surface blood vessels in response to sudden cooling causes an instantaneous and massive increase in blood pressure and heart rate.

Lesson 5: Complacency can be lethal. Jim was a very experienced kayaker, but he let his guard down. We're all capable of making the same mistake - which is a classic one in adventure sports - because rather than making us more alert, experience and familiarity often breed a state of mind that makes it very easy do things like rationalizing a near-lethal decision to paddle unprotected on freezing water.

Cold water doesn’t just prey on unsuspecting newbies. Even if you're a seasoned paddler with plenty of experience, cold water should always be viewed as a potentially lethal environment. As this incident demonstrates, you don't have to be on a difficult and remote 10-mile crossing for cold water to kill you. It can happen right offshore, in a calm, familiar location.

In his article, Jim provides us with a ringside seat to the silk-smooth process by which so many otherwise sensible people rationalize a decision to paddle on very cold water without thermal protection:

“I told myself—I was not going kayaking. I was just going to make a quick ten-minute trial.” “I wasn’t going to leave the shelter of the boat basin. I was merely launching a boat in my own back yard (a familiar nearby marina) as I had launched hundreds of times before.”

Randy Morgart expressed the same view when writing about his near-death experience on the Mississippi River: Cold and Alone on an Icy River “It’s easy to dismiss these [safety] concerns because we have no intention of swimming.”

Major Contributing Factors

Not Dressed For Water Temperature

Unable To Recover From Capsize

Unable to Call For Help

Being Complacent / Overconfident

Paddling Solo